I was glad to spot this collection from the poet and essayist Tony Hoagland in the library. It is provocative, clear-eyed, and flavorful like much of his poetry of social satire published since his chapbook, Hard Rain (Hollyridge, CA 2005).

I can still remember reading Hard Rain for the first time at an outdoor cafe table in Charles Village, in Baltimore, Maryland. His wide-ranging, almost laugh out loud and then cry poetry about America sort of updates Allen Ginsberg’s poem, “America,” across various settings. As Emily Dickinson puts it, the poetry took the top off my head. It opened up vistas.

Hoagland’s Turn Up the Ocean (Graywolf, MN 2022) is a posthumous collection, sad to say. Hoagland passed away from cancer in 2018, based on these poems and prior ones. With this in mind, the collection is clear-eyed in being focused on essential things. It’s happily vibrant, evasive to labels, and the poems stretch toward insight, wit, biting chuckles, pleasure, and moral judgment. His playful, yet exacting, analogies appear – a signature of his poetry since Hard Rain. The play is a little less wild here, which fits the calmer mood of these poems.

I plan to reread the volume before returning it to the library and the next lucky reader, as there are some amazing poems in here. To name a few: “Among the Intellectuals,” “Gorgon,” and “Bible Out of Order.” There are a few chilling poems noting humanity’s rapacious use of the earth and almost fatalist look to the earth’s potential greeny renewal if civilization collapses. There are some tender poems in here on illness, friendship, aloneness, and time’s passage.

There is an atmosphere of someone living into, not shying from or explaining away, their experience. It’s a palpable strength throughout these poems, appearing in a poem title, “Why I Like The Hospital,” with its rue, humor and acceptance. It can be found in a tender introspective poem about how we sometimes over-interpret interactions. Hoagland does not lament or lampoon, but sits with and looks into it in “Mistaken Identity Librarian Syndrome,” as far as he can.

In the poem, “Gorgon,” Hoagland presents an ars poetrica addressed to fellow poets when he says, “the world is a Gorgon.” He then writes, “Your job is to take notes, / to go on looking.”

This does not have to apply solely to writers, but of course, I take it that way. It might apply to anyone, really.

Blessings to Tony Hoagland and his loved ones. I reviewed his Application for Release from a Dream (Graywolf, MN 2015) linked here, some years ago, and that is a valiant and vibrant book. Here, the social wit’s present. The antic energy is more subdued, the tone, more graceful.

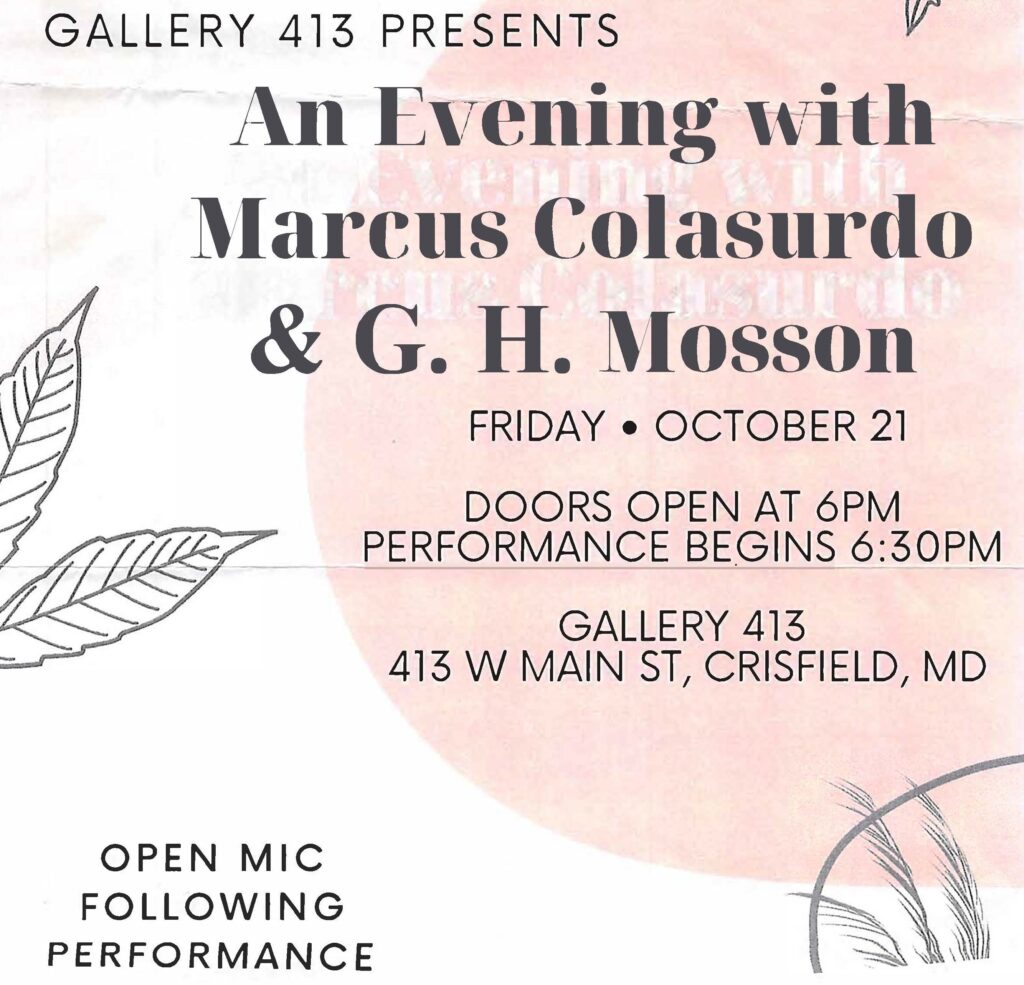

G. H. Mosson

www.ghmosson.com